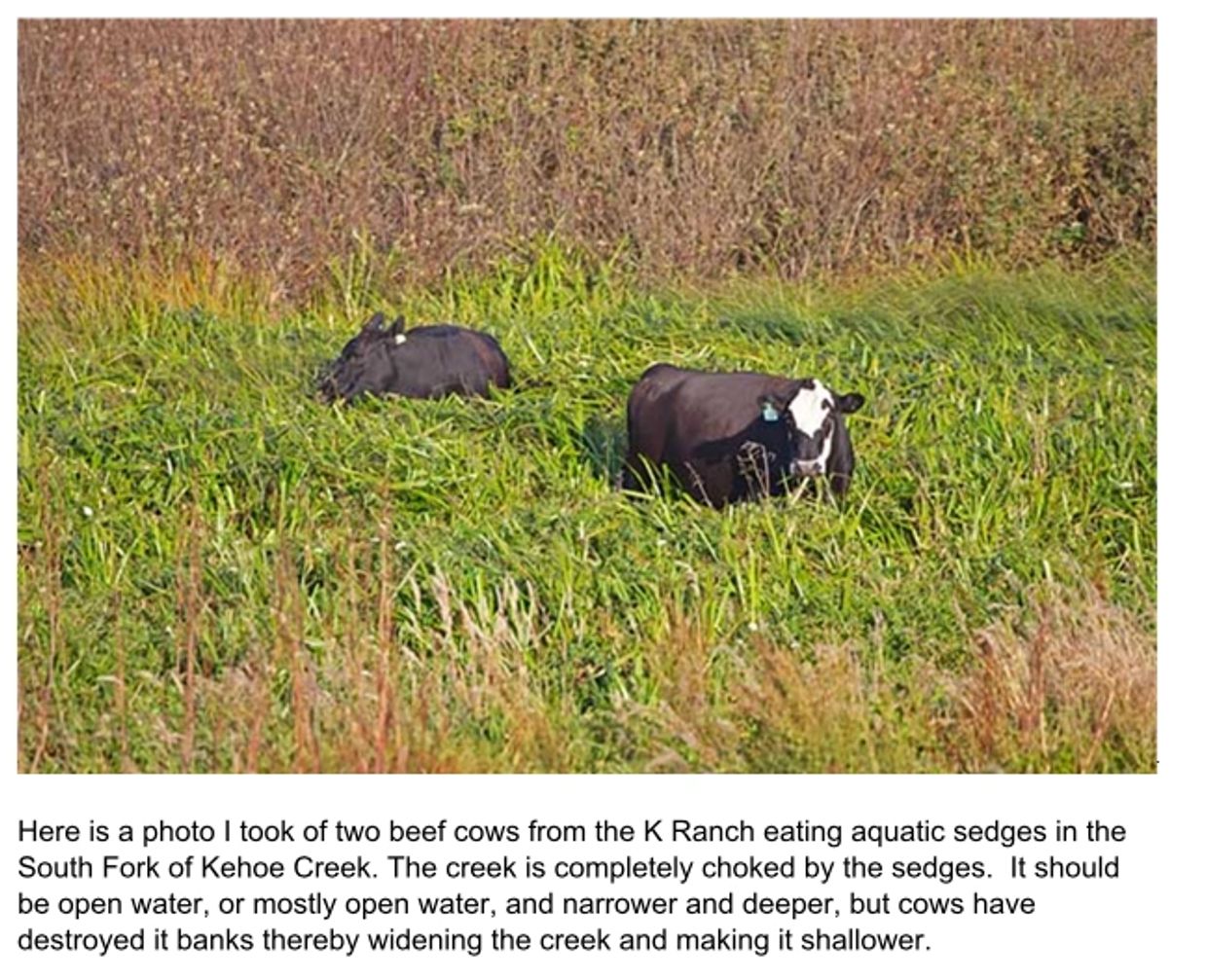

Photo: Jack Gescheidt.

Water Quality

The waters of Point Reyes National Seashore rank in the top 10 percent of U.S. locations most contaminated by livestock feces indicated by E. coli bacteria, according to a report released by Center for Biological Diversity: Cattle Waste Puts California's Point Reyes on 'Crappiest Places in America' List.

Point Reyes National Seashore has been one of the 10 most feces-contaminated locations monitored in California since 2012. The state’s highest reported E. coli level was on a Point Reyes cattle ranch.

The high fecal coliform measures came from wetlands and creeks draining ranches in the popular public Kehoe Beach area of Point Reyes National Seashore. Eight locations in the Olema Valley that receive runoff from cattle ranches in GGNRA also high fecal bacteria levels.

The Park Service’s 2013 Coastal Watershed Assessment for Point Reyes National Seashore (Pawley, A. and M. Lay. 2013. Coastal watershed assessment for Golden Gate National Recreation Area and Point Reyes National Seashore. Natural Resource Report NPS/PWR/NRR-2013/641. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado. Park management ) documented numerous examples of cattle ranching polluting water resources in the park and identified bacterial and nutrient pollution from dairies and ranches as a principal threat to water quality. The Park Service allows dairy ranches to spread liquid cattle manure on grasslands throughout the park. The park report determined that dairies pollute the Drakes Estero, Limantour, Kehoe and Abbots Lagoon areas with high concentrations of fecal coliform. Other studies show that cattle ranches are one of the major contributors of fecal coliform and E. coli to Tomales Bay.

Contamination of water by bacteria is one of the leading causes of impairment in U.S. surface waters. While many bacteria occur naturally in the environment and are an important component of many ecosystem processes, some are of concern because they may cause diseases. These bacteria (E.coli 0157:H7, Salmonella, etc.), as well as viruses (enteroviruses, adenoviruses, etc.) and some protozoans (Cryptosporidium, Giardia, etc.), are referred to as pathogens. Most are found in the gastrointestinal tract of humans and other warm-blooded animals and are shed in the feces.

Find Out More

Concerns about the lack of water quality sampling which has not been carried out in Point Reyes National Seashore since 2013, in spite of very serious water pollution issues at the time, have led In Defense of Animals and Western Watersheds Project to contract an expert to conduct a water quality study. Water sampling from Kehoe Creek and Abbotts Lagoon on January 27 and 28, 2021, showed that bacterial contamination of surface water dramatically exceeded water quality criteria despite the reported implementation by the National Park Service of "Best Management Practices" in drainages impacted by dairy and beef ranches.

Photos on this page by Jim Coda, Tony Sehgal, Skyler Thomas, Jocelyn Knight, and Laura Cunningham.

Too Many Cows

Manure Management

Significant sources of fecal material to lakes and streams includes wastewater discharge, stormwater runoff, and manure runoff. The fecal material in these sources can come from farm animals. Many of the bacteria within feces can survive in environments outside of the animal, thereby elevating bacteria concentrations as they enter a stream.

EPA estimates that one dairy cow can produce about 120 pounds of wet manure in a day, with 80 percent being water. These values indicate that even a small quantity of fecal material escaping into surface water from livestock can cause a substantial impact. Regardless of whether the polluting animals are sick or healthy, they can transmit pathogens in their manure.

Fecal material also contains nutrients and organic matter. Nutrient addition to surface waters, particularly phosphorus and nitrogen, can increase algal growth, decrease water clarity, and increase ammonia concentrations which can be toxic to fish. The increased organic matter also serves as a food source for bacteria and other microorganisms, resulting in lower oxygen levels in the water, and often no oxygen in deeper bottom waters.

During a heavy storm, the precipitation can wash off the land and flow to lower areas, or soak into the soil and either be taken up by rooted vegetation or continue flowing deeper (infiltrating) into the ground, eventually reaching groundwater. Eroded, degraded annual grasslands grazed by cattle may provide less ability to trap pathogens.

Manure recently applied to land prior to a heavy rainfall or to wet ground, can also be washed into nearby streams. Additionally, livestock with access to streams are not only a direct source of manure to the stream but can also erode and damage stream banks as they enter the water, which also results in increased inputs of nutrients and sediment.

When manure escapes from the application site can contaminate surface water and groundwater. Runoff from the farmstead, pastures and fields where manure has been applied can transport sediment, organic solids, nutrients and pathogens to surface waters. Vegetative buffers are not able to effective at capturing most fecal coliform bacteria.

Only removing cattle (both beef and dairy) will remove this health problem from national park watersheds. Climate change may lead to increased winter storm events of larger severity, which could cause more manure runoff into streams along the Pacific Coast.

"Organic" Dairies Place Excess Manure Into Ponds by Kehoe Creek

Dairy liquified manure applications on Point Reyes National Seashore

Jocelyn Knight photos of cattle manure application on National Park land

Too many cows on public park lands

Direct Effects of Grazing

Riparian Areas, Springs, Streams

Direct effects of grazing on riparian areas include increased sediment deposition in streams, water quality impacts such as elevated levels of fecal coliform bacteria, headcutting and localized changes in hydrology, breakdown of stream banks, disturbance and destruction of streambeds, destruction of riparian vegetation, and impairment of the ability of riparian vegetation to recover. Indirect effects include changes to nutrient cycling and thermal effects, and increase risks for spread and establishment of invasive species and algal blooms.

Mountains of Manure Management

Only Removing Cattle From the Seashore Will Improve Water Quality

We have seen ranches in Point Reyes National Seashore, including areas impacting Kehoe Creek, allow manure spreading by various trucking means across pastures. These appear to show sludge-slurry trucks spraying fields, trucks piping manure slurry from holding ponds, trucks releasing manure onto a field, and a liquified manure sprinkler system on a pasture.

How are these methods compatible with a national park unit? What are the human health hazards of such methods? The park service needs to describe each method for disposing of manure on each ranch, as well as the impacts to wildlife, biological resources, sensitive species, native plant communities, visitor experience, water quality, and human health. How much manure is spread on pastures, grasslands, or rare plant communities? When are these manure spreading operations undertaken—spreading manure in the fall before and during rain storms can have serious runoff problems into streams and the ocean.

Water quality testing in all water bodies in the park units should occur quarterly because pollution levels will vary based on certain variables, such as the location of cattle on a ranch in terms of which pastures they are in and not in, and the effect of seasonal variations in water levels or flows which would cause pollution levels to vary. The park service should conduct a cumulative watershed effects analysis for the watersheds in the project area, including a water balance of the water removed from the watershed to water the livestock as well as to dilute the manure to allow manure spreading in the park.

Photo Gallery

1/6

Clean Water is a Must for Human Health

Additional Information

Water quality is an issue in the annual grasslands. Sediment, nutrients, pathogens and heat are potential water pollutants that may be associated with grazing in annual grassland watersheds. In 2004, California’s State Water Resources Control Board adopted policies for regulating non-point source pollution. These policies affect landowners and agricultural producers, including range livestock operations. This new policy replaced a voluntary, education-supported program with regulatory programs, such as implementation of total maximum daily load (TMDL) requirements for non-point source discharges from agricultural lands, including grazing land. The NPS should analyze non-point source pollution on all ranches, and impacts to surrounding park lands and waters.

The high fecal coliform measures came from wetlands and creeks draining ranches in the popular public Kehoe Beach area of Point Reyes National Seashore. Eight locations in the Olema Valley that receive runoff from cattle ranches in Golden Gate National Recreation Area also high fecal bacteria levels.

Prohibiting livestock from accessing streams and other surface waters is another effective way to reduce water pollution and also maintain stream habitat. Fencing off areas that have direct stream access keep livestock from trampling stream banks, increasing erosion, and destroying vegetation along the stream bank. It also prevents livestock from defecating directly into the water. We saw no fences along Kehoe Creek or several other creeks, and manure spreading happens within meters of creeks.

When manure escapes from the application site can contaminate surface water and groundwater. Runoff from the farmstead, pastures and fields where manure has been applied can transport sediment, organic solids, nutrients and pathogens to surface waters. Vegetative buffers are not able to effective at capturing most fecal coliform bacteria. Only removing cattle (both beef and dairy) will remove this health problem from national park watersheds. Climate change may lead to increased winter storm events of larger severity, which could cause more manure runoff into streams along the Pacific Coast.

As E. coli concentrations increase in surface waters, it is likely that some type of fecal contamination has occurred. When the concentrations exceed water quality standards, people are at a greater risk of coming into contact with pathogens. The most common illness associated with exposure (swimming, ingestion) to fecal-contaminated water is gastroenteritis, which can result in nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, fever, headache, and diarrhea. Swimming in impacted waters can also lead to eye, ear, nose, skin, and throat infections and respiratory illnesses. In rarer cases, contaminated waters can lead to more serious conditions such as hepatitis, salmonellosis, or dysentery. Agricultural waste products are posing a health hazard for beachgoers at some parts of the National Seashore.

Cattle Water Pollution

Cows on the Coast

Public Lands Leases

Public Lands Leases

Beef cattle along Drake's Estero. Photo: Jocelyn Knight.

Public Lands Leases

Public Lands Leases

Public Lands Leases

Beef cow by the parking lot at Drake's Estero, Point Reyes National Seashore. Photo: Jocelyn Knight.

Photo: Jim Coda.

March 5, 2021 Press Release

Water Contamination from Cattle Ranching at Point Reyes National Seashore Causes Outrage

Contacts: Laura Cunningham, Western Watersheds Project, 775-513-1280, lcunningham@westernwatersheds.org

Lisa Levinson, In Defense of Animals, 215-620-2130, lisa@idausa.org

Jim Coda, former National Park Service attorney, (415) 602-6967

POINT REYES, Calif. (March 4, 2021) — Water sampling from Kehoe Creek and Abbotts Lagoon on January 27 and 28, 2021, showed that bacteria contamination of surface water dramatically exceeded water quality criteria despite the reported implementation by the park service of waste management actions in drainages impacted by dairy and beef ranches. Concerns about the lack of water quality sampling which has not been carried out in Point Reyes National Seashore since 2013, in spite of very serious water pollution issues at the time, have led In Defense of Animals and Western Watersheds Project to contract an expert to conduct a water quality study.

Water monitors also made a short video (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k_zN-pDFbzI) about the situation and the water sampling, produced by Jack Gescheidt of Tree Spirit Project and Tony Sehgal of Silver Reactions Media.

Bacteria results for the South Fork of Kehoe Creek were 30 times the allowable limit for applicable water quality standards for the bacterium Escherichia coli (E. coli) on January 27, and 20 times the limit on January 28. Kehoe Creek drains to Kehoe Lagoon at Kehoe Beach and, with heavy rains, the lagoon flows to the ocean. The Lagoon and the ocean are popular recreational spots with direct human contact, which triggers more stringent water quality criteria. A sample was taken from the Lagoon on January 28 and it exceeded E. coli limits by a factor of 40, and exceeded enterococci limits by a factor of 300 (Enterococcus is another large genus of bacteria).

“I am troubled that measures to try to stop this chronic cattle water pollution in these park units are not working,” noted Laura Cunningham, California Director at Western Watersheds Project. “The mere band-aids currently in place to try to stop the cow manure entering these park waters and coastal habitats for the sake of imperiled species appear to be entirely ineffective.”

Both types of bacterial pollutants pose a hazard to human health and the environment. E. coli is a fecal contaminant that causes food poisoning while enterococci can cause meningitis, urinary tract infections and other diseases in humans. The latter has a high level of antibiotic resistance and is responsible for causing epidemic outbreaks in hospitals over the past two decades. In addition, dairy cattle have for years infected the native Tule elk with Johne’s disease from a Mycobacterium, with no action to end this transfer by the park service.

Abbotts Lagoon is a popular place for water activities. New water samples were taken from an unnamed creek at the Lagoon that flows across lands leased by I Ranch into the upper chamber of the three-chambered lagoon. Samples were taken on both January 27 and 28. On January 27 the unnamed creek exceeded E. coli limits by a factor of 20 and enterococci limits by a factor of 60. On January 28 it exceeded E. coli limits by a factor of 2 and enterococci limits by a factor of 70.

These test results are consistent with National Park Service test results from 1999 to 2013, yet no signage has been posted to date by the National Park Service warning park visitors to stay out of these hazardous waters.

This year’s findings come despite warnings by the Center for Biological Diversity which in 2017 ranked Point Reyes as having among the top ten most-polluted waters in the U.S. owing to contamination by fecal coliform bacteria from cattle manure (https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/news/press_releases/2017/point-reyes-11-21-2017.php).

Lisa Levinson, Wild Animals Campaigner for In Defense of Animals, said, “We were shocked to discover that the National Park Service hasn’t performed its own water quality tests since 2013, especially since the last one showed high levels of pollutants. That’s why we took the initiative to acquire new water quality data to review before the record of decision for the proposed General Management Plan Amendment is signed. The California Coastal Commission needs this data to accurately assess the environmental risks involved in moving forward with this disastrous plan. Clearly, current commercial ranching activities are harming wild animals and human recreation ability in the park. Increased ranching detailed in the plan should be off the table considering the further environmental damage it will undoubtedly cause this sensitive and priceless park unit containing endangered, rare, and endemic native species.”

Dairies on the Seashore collect manure and urine in holding ponds and then during the dry season spread it onto park lands used as grazing pastures. During and shortly after rainstorms, some of the manure washes into adjacent streams and creeks and into the coastal lagoons and ocean. This can cause a spike in dangerous bacterial contaminants in publicly accessible waters in the Seashore. These waters are also inhabited by the federally threatened Central Coast steelhead trout, endangered coho salmon, and endangered California red-legged frog.

“The January water quality monitoring clearly shows that harmful bacteria levels did not end in 2013,” said Cunningham. “They are still occurring.”

Pacific Ocean species are in urgent need of better conservation measures and clean water, such as the Southern population of orca, blue whale, gray whale, northern elephant seal, Steller sea lion, Southern sea otter, Western snowy plover, brown pelican, steelhead trout, coho salmon, tidewater goby, black abalone, and many others. Declining coastal habitats such as eelgrass beds—marine plants that form rich meadows that are nurseries to many species of fish, invertebrates and other sea life—are also threatened by runoff pollution from farms in Point Reyes.

Samples were also taken at two sites in drainages with light to medium use by cattle raised for beef. The first site, East Schooner Creek, was slightly above the Clean Water Act standard for E. coli, and four times the standard for enterococci. The second site, Schooner Creek, was measured just below where East Schooner Creek joins it. Schooner Creek is tidally affected so an E. coli criterion is not available, but it exceeded the enterococci criterion by 3 to 5 times. Macronutrient pollution tests of surface waters for nitrogen and phosphorus were also measured by the monitoring team. When cattle manure and urine is washed into waters it acts as artificial fertilizer, causing excess growth of algae and harmful algal blooms in park-managed waters. This type of water pollution appears to be persisting at concentrations similar to levels before cattle waste management actions were reportedly implemented.

“Current waste management actions do not seem to have any appreciable effect to mitigate macronutrient pollution by farms at Point Reyes,” said Levinson. “The measured nutrient pollution explains the increased frequency and intensity of harmful algal blooms in Abbotts and Kehoe lagoons, an impact that will only worsen with climate change.”

These findings come at a contentious time, as plans are currently being considered for how the Seashore and adjacent northern District of Golden Gate National Recreation Area will be managed for decades to come. At the heart of the controversial planning process is a General Management Plan amendment that calls for prolonged cattle grazing and dairying, increased agricultural diversification, and even shooting of native Tule elk owing to claims that they compete for grass with the cows — despite their status as an at-risk, protected species that is vastly outnumbered by cattle.

While tougher implementation of additional cattle waste management actions and “best management practices” could potentially reduce bacteria contamination to waters and the ocean, observers and organizations are very concerned about the lack of effectiveness of park service actions to reduce these significant exceedances enough to meet applicable criteria, reduce harm to rare species and habitats, and prevent human health emergencies.

“Reductions in the localized abundance of cattle waste — and the cattle producing it — will be necessary as an urgent measure to adequately protect water quality at Point Reyes National Seashore,” said Cunningham.

####

Water Testing Report Available by Request (see contact information above) http://bit.ly/PtReyesWaterPollution

In Defense of Animals is an international animal protection organization with over 250,000 supporters and a 37-year history of protecting animals’ rights, welfare, and habitats through education, campaigns, and hands-on rescue facilities in India, South Korea, and rural Mississippi. www.idausa.org

Western Watersheds Project is a nonprofit environmental conservation group that seeks to protect and restore western watersheds and wildlife through education, public policy initiatives, and legal advocacy. https://www.westernwatersheds.org

Fecal Bacteria Poisons Point Reyes Beaches

Kehoe Lagoon seethes with 300 times the acceptable amount of Enterococcus, E. Coli's nasty bacterial cousin. Public records show that Park Service administrators and the California Regional Water Quality Control Board have long known that astronomically high levels of microorganisms flow directly from livestock into the Park’s recreational and fishing waters. And these agencies have done nothing to effectively eliminate the source of the potentially lethal bacterial invasions.